The Streak

Up until the 1941 season the modern day (since 1903) record for hits in consecutive games was 41 by George Sisler of the St. Louis Browns in 1922, whilst the all-time record was 45 by Wee Willie Keeler of the Baltimore Orioles spread over the last game of the 1896 season and the first 44 games of the 1897 season.

On 15th May, DiMaggio got a hit against White Sox pitcher Eddie Smith which started his historic hitting streak.

Initially, DiMaggio showed little interest in breaking Sisler’s record, saying:

“I’m not thinking a whole lot about it. I’ll either break it or I won’t.”

As he approached Sisler’s record, DiMaggio showed more interest:

“At the start I didn’t think much about it but naturally I’d like to get the record since I am this close.”

On 1st July DiMaggio broke Keeler’s record with a homer against the Red Sox.

On 17th July at Cleveland Stadium, DiMaggio’s streak was finally snapped at 56 games, thanks in part to two backhand stops by Indians third baseman Ken Keltner.

DiMaggio batted .408 during the streak, with 15 homers and 55 RBI. The day after the streak ended, DiMaggio started another streak that lasted 16 games. The distinction of hitting safely in 72 of 73 games is also a record.

The closest to breaking this streak was Pete Rose of the Cincinnati Reds in 1978 who hit in 44 straight.

The best streak since the turn of the century is Jimmy Rollins’ of 38 games, spread over 2005 and 2006 for the Phillies.

Strangely enough Joe’s brother Dom holds the Red Sox record for the hits in consecutive games with 34, in 1949.

This was not the only incredible feat by a hitter in 1941 however.

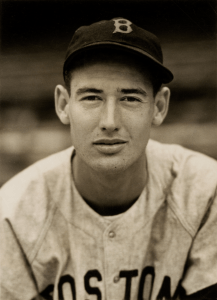

The splendid splinter and his 1941 season

Ted Williams debuted in the Majors for the Red Sox in 1939 and quickly established himself as one of the best hitters in the game, getting 31 home runs alongside leading the league in RBIs and total bases in his rookie year.

It is however his 1941 year that would go down in baseball lore, as arguably the greatest out and out hitter the game ever saw, embarked on a memorable season that has not been matched since.

Williams’ average slowly started to rise during May, and from 15th May he had a 22-game hitting streak and by 25th May he was hitting at an average of .430.

By the All-Star game he was hitting .406 with 62 RBIs and 16 homers.

In late August, Williams was hitting .402. Williams said that “just about everybody was rooting for me” to hit .400 in the season, even Yankee fans, who gave pitcher Lefty Gomez a “hell of a boo” after walking Williams with the bases loaded after Williams had gotten three straight hits one game in September.

In mid-September, Williams was hitting .413, but dropped a point a game from then on.

Before the final two games on 28 September, a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Athletics, he was batting .39955, which would have been officially rounded up to .400.

Red Sox manager Joe Cronin offered him the chance to sit out the final day, but he declined, saying:

“If I’m going to be a .400 hitter I want more than my toenails on the line.”

Williams went 6-8 over the two games, finishing the season at .406.

Sacrifice flies were counted as at-bats in 1941; under today’s rules, Williams would have hit between .411 and .419, based on contemporaneous game accounts.

Along with his .406 average, Williams also hit 37 home runs and batted in 120 runs, missing the triple crown by five RBI.

In case you’re wondering, his on base percentage that year was an incredible .553 over 456 at bats which still stands as a single season American League record with only Barry Bonds above him all time with .609 in 2004 and .582 in 2002.

His OPS (on base plus slugging) that year was 1.287 and that is the 7th best single season OPS with only Barry Bonds and Babe Ruth (3 times each) above his 1941 mark. In fact, the top 12 best single season marks of OPS comprise of these three players with Bonds being on there 4 times, Ruth 6 and Williams twice.

It was the first time since 1930 when Bill Terry of the New York Giants batted .401 that someone had batted .400 in a MLB season. No-one has done it since.

The closest to doing it since was Tony Gwynn of the San Diego Padres who batted .394 in the 1994 season where of course the Baseball season was stopped due to a player’s strike causing there to be no postseason in MLB for the first since 1904.

The fall of the Iron Horse

On 2nd June 1941, Lou Gehrig finally died at his home of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Upon hearing the news, Babe Ruth and his wife Claire went to the Gehrig house to console Lou’s wife Eleanor.

Mayor Fiorello La Guardia ordered flags in New York to be flown at half-staff, and Major League ballparks around the nation did likewise.

Following the funeral across the street from his house, Gehrig’s remains were cremated and interred on 4th June at Kensico Cemetery in Valhalla, New York, which is 21 miles north of Yankee Stadium.

Lou Gehrig and Ed Barrow (former Yankee General Manager) are both interred in the same section of Kensico Cemetery, which is next door to Gate of Heaven Cemetery, where the graves of Babe Ruth and Billy Martin (former Yankee player and manager) are both located in Section 25.

The Gehrigs had no children during their eight-year marriage. Eleanor never remarried, and was quoted as saying:

“I had the best of it. I would not have traded two minutes of my life with that man for 40 years with another.”

She dedicated the remainder of her life to supporting ALS research. She died 43 years after Lou on 06 March 1984 and was interred with him in Kensico Cemetery.

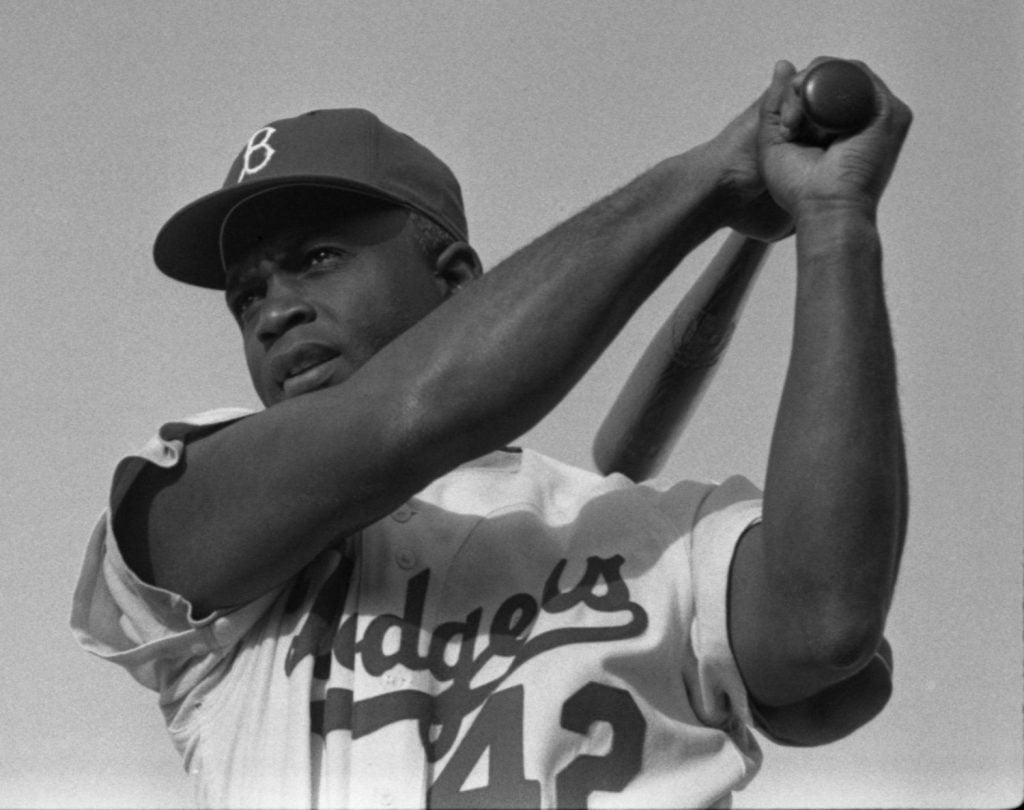

Jackie Robinson

15th April 1947 – Arguably the most momentous day in baseball history as baseball finally had a player playing in the Majors who was black, Jackie Roosevelt Robinson, for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

There were attempts at getting black players into MLB before Robinson, including Moses Fleetwood Walker who played one season as catcher in the majors for the Toledo Blue Stockings, a club in the then called American Association.

Unfortunately, racism, even from his own teammates, forced him to go to the minor leagues where he played until 1889, when an unofficial “Colour Barrier” was erected saying that no MLB team would have a black player on their staff.

There was another instance of a black player playing for a MLB club when John McGraw in 1901 tried to pass off a player of African American descent by the name of Charlie Grant, as a Native American named “Tokohama”.

However, his plan unravelled in Chicago when White Sox President Charles Comiskey recognised him and objected to him playing.

After the legendary New York Giants manager John McGraw died in 1934 his wife found amongst his possessions a list of all the black players McGraw wished he could have signed.

You may know that there was a Negro Baseball League between 1920 and 1951. They produced a fiery brand of baseball and it was a successfully run business. Possibly the two greatest stars of the Negro Baseball League era were pitcher Satchel Paige and catcher Josh Gibson. The latter was known as “the black Babe Ruth” although some called Babe Ruth “the white Josh Gibson”.

You may remember from previous stories a man by the name of Branch Rickey. He is, in my view, just as important in this story as Jackie Robinson is because without Rickey it would not have happened. In 1945, Rickey wanted to bring a black ball player to his club, the Brooklyn Dodgers, and chose Robinson out of a list of promising black players and decided he would interview him.

Robinson was known to be a feisty player and Rickey was understandably worried about his reactions when the inevitable racial taunts and abuse came his way.

They met on 28 August 1945 and Rickey asked him if he would not react when the inevitable abuse came his way and Robinson was aghast, saying:

“You want someone who is afraid to fight back?”

Rickey responded:

“No. I want someone (a black ballplayer) who has guts not to fight back.”

Robinson would not immediately report to the Dodgers; he would spend the 1946 season with the Montreal Royals who were the Dodgers AAA team.

Robinson would finish that season with a .349 batting average and was voted the league’s Most Valuable Player.

Although he often faced hostility while on road trips (the Royals were forced to cancel a Southern exhibition tour, for instance), the Montreal fan base enthusiastically supported Robinson.

Whether fans supported or opposed it, Robinson’s presence on the field was a boon to attendance; more than one million people went to games involving Robinson in 1946, a stunning figure by International League standards.

Robinson was a second baseman, however the Dodgers already had an everyday second baseman, Eddie Stanky, so he was trained to play first base in time for the 1947 MLB season.

Robinson’s promotion to the Dodgers was met with mixed reactions at best shall we say, even amongst some in the Dodgers clubhouse and even, rumour has it, led to some players signing a petition saying they would not play with Robinson.

The Dodgers management decided to take action against this.

Manager Leo Durocher calling a team meeting said to the whole team (possibly my favourite quote ever):

“I do not care if the guy is yellow or black, or if he has stripes like a f*****g zebra. I’m the manager of this team, and I say he plays. What’s more, I say he can make us all rich. And if any of you cannot use the money, I will see that you are all traded.”

Some other teams, notably the Cardinals, were not best pleased at (in their minds) having Robinson forced upon them. The Cardinals even threatened to strike if Robinson played.

Even in games the Cardinals showed their displeasure. One incident saw one of their players, Enos Slaughter, spiking Robinson when the former was running to 1st which left a 7-inch gash on Robinson’s leg.

One other person who was not happy about it either was Philadelphia Phillies manager Ben Chapman who hurled racial taunts at Robinson early in the season before being forced to publicly apologise in front of the media with Robinson by his side.

Rickey later recalled that Chapman “did more than anybody to unite the Dodgers. When he poured out that string of unconscionable abuse, he solidified and united thirty men.”

Robinson finished the season having played in 151 games for the Dodgers, with a batting average of .297, an on-base percentage of .383, and a .427 slugging percentage.

He had 175 hits, scored 125 runs, including 31 doubles, 5 triples, and 12 home runs, with 48 RBIs. Robinson led the league in sacrifice hits, with 28, and in stolen bases, with 29.

His cumulative performance earned him the inaugural Major League Baseball Rookie of the Year Award (separate National and American League Rookie of the Year honours were not awarded until 1949). He would go on to win the NL MVP in 1949.

He also guided the Dodgers to the World Series that year where they lost 4-3 to the Yankees. He would play in a further 5 World Series, losing 4 and winning 1 in 1955.

Robinson would retire in 1956 and eventually died in 1972 aged 52 of a heart attack.

Robinson’s story was dramatized in a 2013 film called 42, starring Chadwick Boseman as Jackie Robinson and Harrison Ford as Branch Rickey. If you have not seen it I implore that you do so.

On 15 April 1997 Robinson’s jersey number 42 was retired across all MLB teams.

15 April 2004 saw the first Jackie Robinson Day in MLB. It is commemorated by every player, coach and manager of all teams wearing the number 42 in Jackie’s honour for their games that day.

Babe Ruth dies

Twelve days after the debut of Jackie Robinson, 27th April 1947, was a day proclaimed as Babe Ruth Day throughout the majors, celebrated at all ball major ballparks, with the most significant observance to be at Yankee Stadium.

A number of teammates and others spoke in honour of Ruth, who briefly addressed the crowd of almost 60,000 but he was very ill by this time with throat cancer.

Surgery had slowed the disease but damaged his larynx. Here is his heartbreaking speech:

Around this time developments in chemotherapy offered some hope. The doctors had not told Ruth that he had cancer because of his family’s fear that he might do himself harm, but before his death Ruth had surmised the truth. By the last weeks of his life he was barely able to speak.

On 13 June 1948, Ruth visited Yankee Stadium for the final time in his life, appearing at the 25th anniversary celebrations of “The House that Ruth Built”.

By this time, he had lost much weight and had difficulty walking.

Introduced along with his surviving teammates from 1923, Ruth used a bat as a cane.

His condition gradually became worse; only a few visitors were allowed to see him, one of whom was National League president and future Commissioner of Baseball Ford Frick.

“Ruth was so thin it was unbelievable. He had been such a big man and his arms were just skinny little bones, and his face was so haggard”, Frick said years later.

Thousands of New Yorkers, including many children, stood vigil outside the hospital in Ruth’s final days.

On 16th August 1948 at 8:01 pm, Ruth died in his sleep at the age of 53.

The greatest baseball player and one of the greatest sportsman ever, was dead.