The “Curse of the Bambino”

The so-called “Curse of the Bambino” refers to the sale of Babe Ruth from the Red Sox to the Yankees in 1920 for $125,000 with a promise of a $300,000 personal loan, and the subsequent immediate rise of the Yankees which has seen 29 World Series titles and zero after the sale for the Red Sox until 2004.

The Yankees had not even been in the World Series before acquiring Ruth whilst the Red Sox had been in 5, winning all of them.

Before the Red Sox ended the curse in 2004 they had lost all 4 World Series they had played in after the sale of Ruth; all in 7 games, in 1946, 1967, 1975 and 1986.

Although it had long been noted that the selling of Ruth had been the beginning of a decline in the Red Sox’ fortunes, the term “Curse of the Bambino” was not in common use until the publication of the book “The Curse of the Bambino” by Dan Shaughnessy in 1990.

What I will tell you in this section is largely taken from Shaughnessy’s book as well as his 2005 book “Reversing the Curse.”

You might ask why the Red Sox sold Ruth, such a prized asset, to the Yankees. Well there are varying theories. Some are more believable than others.

Ruth’s reputation with the Yankees was of being a big drinker, partyer and womaniser and occasional refusal to always show his masters obedience. The latter something he had been like since childhood. There are stories that suggest he was similar with the Red Sox so it is possible that the management and owner Harry Frazee had had enough.

I’m more prepared to believe that theory rather than the legend I am about to tell you.

The legend is that the then Red Sox owner and theatrical producer Harry Frazee used the proceeds from the sale to finance the production of a Broadway musical, usually said to be “No, No, Nanette”.

In fact, Frazee backed many productions before and after Ruth’s sale, and “No, No, Nanette” did not see its first performance until five years after the Ruth sale and two years after Frazee sold the Red Sox.

In 1921, Red Sox manager Ed Barrow left to take over as general manager of the Yankees. Other Red Sox players were later sold or traded to the Yankees as well.

Neither the lore, nor the debunking of it, entirely tells the story.

As Leigh Montville wrote in “The Big Bam: The Life and Times of Babe Ruth”, “No, No, Nanette” had originated as a non-musical stage play called “My Lady Friends”, which opened on Broadway in December 1919.

That play had indeed been financed as a direct result of the Ruth deal. Various researchers, including Montville and Shaughnessy, have pointed out that Frazee had close ties to the Yankees owners, and that many of the player deals, as well as the mortgage deal for Fenway Park itself, had to do with financing his plays.

So if you’ve ever wondered what started the rivalry between the Red Sox and the Yankees, this is it!

First player in MLB history to die on the field

In 1920, Cleveland Indians shortstop Ray Chapman was hit in the head by a pitch by Yankees pitcher Carl Mays and he eventually died soon after from his injuries.

At the time of Chapman’s death. part of every pitcher’s job was to dirty up a new ball the moment it was thrown onto the field.

They smeared it with dirt, liquorice, and tobacco juice; it was deliberately scuffed, sandpapered, scarred, cut, even spiked.

The result was a misshapen, earth-coloured ball that travelled through the air erratically, tended to soften in the later innings, and as it came over the plate, was very hard to see.

They wouldn’t throw it out of the game, only used three or four balls a game, now they use 60 or 70.

This practice is believed to have contributed to Chapman’s death.

He was struck with a pitch by Carl Mays on 16 August 1920, in a game against the New York Yankees at the Polo Grounds.

Mays threw with a submarine delivery (an example of this style of throwing motion is shown here).

Mays was known to be hot headed and he was angry that Chapman was crowding the plate. Mays let loose a high fastball that he claimed was in the strike zone but that Chapman apparently never saw.

Eyewitnesses recounted that Chapman never moved out of the way of the pitch, presumably unable to see the ball.

“Chapman didn’t react at all,” said Rod Nelson of the Society of American Baseball Research. “It was at twilight and it froze him.”

The sound of the ball smashing into Chapman’s skull was so loud that Mays thought it had hit the end of Chapman’s bat, so he fielded the ball and threw to first base.

Mike Sowell’s book, “The Pitch That Killed”, however, states that first baseman Wally Pipp caught Mays’ throw to first and then realized something was very wrong. Chapman never took any steps, but rather slowly collapsed to his knees and then the ground with blood pouring out of his left ear.

The umpire quickly called for doctors in the stands to come to Chapman’s aid. Eventually Chapman was able to stand and try to walk off the field, but he could not speak when he tried to do so, but only mumbled.

As he was walking off the field his knees buckled and he had to be assisted the rest of the way. He was replaced by Harry Lunte for the rest of the game, which the Indians won 4-3. Chapman died 12 hours later in a New York City hospital, at about 4:30am.

In tribute to Chapman’s memory, Cleveland players wore black arm bands, with manager Tris Speaker leading the team to win both the pennant and the first World Series Championship in their history.

Rookie Joe Sewell took Chapman’s place at shortstop, and went on to have a Hall of Fame career, which he coincidentally concluded with the Yankees.

After the incident the umpires had orders to substitute the ball if the ball got dirty for a fresh ball. This and the ban of certain pitches (such as the Spitball, Emery Ball and Shine Ball) were done in the hope that this horrible incident never happens again.

Chapman is to this day the only MLB player to die as a result of on field injuries.

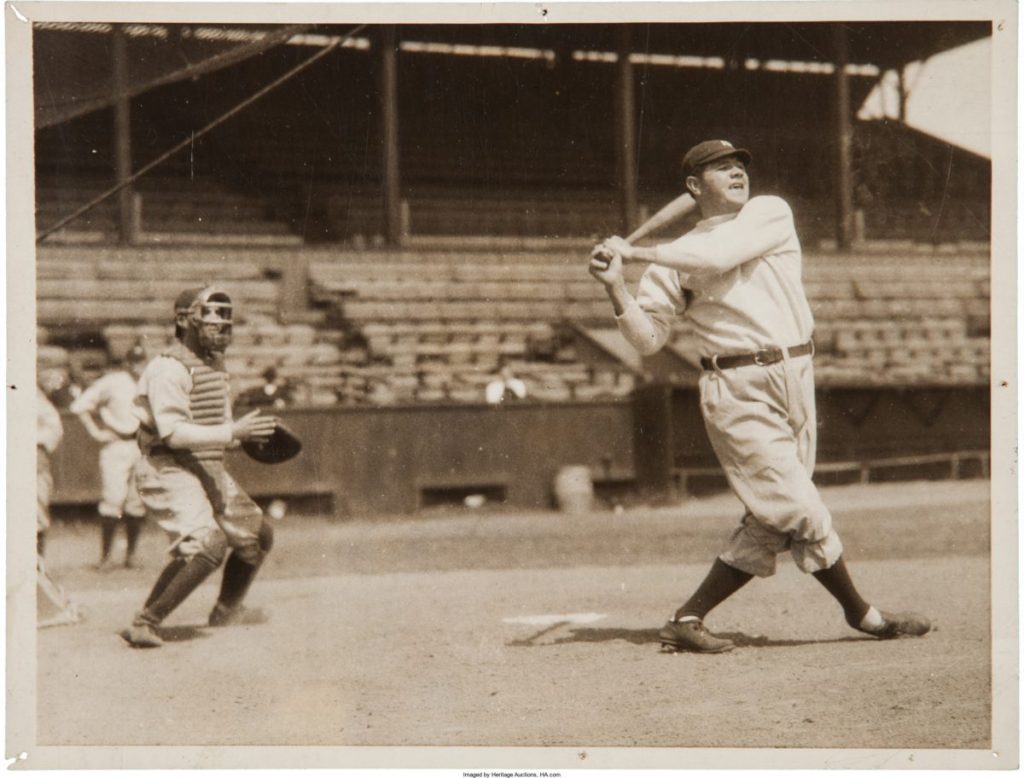

Babe Ruth and the Emergence of the Home Run

In 1920, Babe Ruth hit an astonishing 54 home runs breaking the single season home run record that he set himself the year before when he hit 29 for the Red Sox.

This is when the game started to change. This incredible emergence of Ruth as a converted hitter came at the perfect time for the game.

As you will know from my last piece 1919 saw the fixing of the World Series and Ruth came just as all that was going on to help move people away from all that mess.

It was most definitely fortuitous that Ruth came along and lightened the game up for a disillusioned public.

Until 1920 and the age of Ruth the tactic of smallball was largely used. Basically no pitcher was ever worried about a run being scored if there was no-one on base. Runs in those days were collated usually one base at a time via either hits, bunts, hit and run plays, steals or double steals. The New York Giants under John McGraw were experts at this style.

However, Ruth’s emergence signalled a shift into how baseball was to be thought of and played from then on.

Bats got better for hitters and the balls after Ray Chapman’s death were made livelier by winding the yarn inside the ball tighter, which going with the fact the balls were now replaced after a ball got dirty and certain pitches were outlawed meant the balls were easier to see for the hitters and more and more home runs were hit from there on in.

So basically the balance shifted and it became a hitter’s game rather than a pitcher’s game which it had been up until that point.

A stat that illustrates this point nicely is that between 1910-1920 8 pitchers won 30 or more games in a season. Since then however there have been just 3 and they were Lefty Grove (31) in 1931, Dizzy Dean (30) in 1934 and Denny McLain (31) in 1968.

In 1921, Ruth broke the single season home run record for the third straight year by hitting 59 and also passed Roger Connor’s all-time home run mark of 138.

In 1927, Babe Ruth broke the single season home run record for the fourth time by hitting an extraordinary 60 home runs which was more than any other American League team managed as a whole.

By September, Ruth was carrying his bat around the bases to thwart souvenir seekers. When he hit number 56 on 22 September an over eager boy ran out to grab it, Ruth then dragged the bat and the boy behind him as he crossed home plate.

Subway Series

Between 1921-1923 all 3 World Series were Subway Series, i.e. between 2 New York teams, the Giants and the Yankees.

In the 1921 World Series, Ruth was hurt for part of the series and the Giants won the series 5-3.

In the 1922 World Series, Ruth was fit throughout (but was coming off a bad season as he was often suspended for his various misdeeds) but the Giants neutralised him as John McGraw told his pitchers to pitch slow stuff in the dirt as Ruth would be swinging at anything.

This proved successful, Ruth struggled, going 2-17 with 2 walks and the Giants swept the series 4-0. McGraw was gleeful saying that once again he had “the big monkey’s number. Just pitch him low curves and slow stuff, and he falls all over himself.”

Carmen Hill, a Giants pitcher of that era, said that:

“There’s no question that Ruth was the greatest fastball and curveball hitter in the business. He could not hit slow stuff; he just couldn’t hit it.”

In the 1923 World Series Ruth was more successful, hitting 3 home runs in 6 games with an OPS of 1.556 as the Yankees won the last 3 games to win their first World Series 4-2.

The House That Ruth Built

The two New York teams, the Giants and the Yankees shared the same ground initially, the Polo Grounds from 1913-1922.

However, after Ruth joined the Yankees in 1920 the Yankees outgrew the Giants in the Polo Grounds, including attracting a million fans in that 1920 season to the Polo Grounds to watch them which was the first time that had happened, so they were losing New York to the Ruth and the Yankees which drove the Giants and their manager John McGraw potty.

McGraw didn’t like Babe Ruth either so eventually things came to a head and McGraw asked the Yankees to leave.

The Yankees built their own stadium, Yankee Stadium, in 1922 and 1923 and it was entirely out of the pocket of their owner Jacob Ruppert for a fee of $2.4m which is about $35m in today’s money.

It was opened in time for the start of the 1923 season and it was nicknamed “The House That Ruth Built” as it was said to be built to fit all of the fans that wanted to see Ruth play.

The Farm System – Branch Rickey

Faced with a weak team, the St. Louis Cardinals General Manager Branch Rickey resolved that rather than try to pay for stars he would simply grow his own. The result was the farm system, minor league teams linked together and run purely to produce stars for the big time.

The farm system as it is recognised today was invented by Branch Rickey, who – as field manager, general manager, and club president – helped to build the St. Louis Cardinals dynasty during the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

When Rickey joined the team in 1916, players were commonly purchased by major league teams from independent, high-level minor league clubs.

Rickey, a keen judge of talent, became frustrated when the players he had scouted at the A and AA levels were sold by those independent clubs to wealthier rivals such as the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants.

With the support of Cardinal owner Sam Breadon, Rickey devised a plan whereby St. Louis would purchase and control minor league teams from Class D to Class AA (the highest level at the time), thus allowing them to promote or demote players as they developed, and “grow” their own talent.

The Farm System was a spectacular success. Soon Rickey had 800 players under contract on 32 teams.

He would say that “there is quality in quantity.” The Farm System made Rickey a rich man and he personally got 10 cents on the dollar for every player he sold.

The Cardinals won nine National League pennants and six World Series championships between 1926 and 1946, proving the effectiveness of the Farm System concept.

The second club to fully embrace such a system, the New York Yankees, used it to sustain their dynasty from the mid-1930s through the middle of the 1960s.

The teams that ignored the farm system in the 1930s and early 1940s (such as the Philadelphia A’s, Phillies and the Washington Senators) found themselves falling on hard times.

When Rickey moved to the Brooklyn Dodgers as president, general manager and part-owner in 1943, he proceeded to build a hugely successful farm system there as well.

At the Dodgers he hired a statistician called Allan Roth who, alongside Rickey, helped promote the idea that on-base percentage was a more important stat than batting average.

Grover Cleveland Alexander

In 1926 a 39-year-old pitcher named Grover Cleveland Alexander was playing for the struggling Chicago Cubs.

He had a wonderful career, joint 3rd in all-time wins for pitchers with Christy Mathewson with 373 but was at the wrong end of his career.

He, like many MLB players, served for the Allies in World War I and whilst serving in France he was exposed to German mustard gas and a shell exploded near him, causing partial hearing loss and triggering the onset of epilepsy.

As a result of this, after returning from the War, he suffered from shell shock and epileptic seizures. He was already a heavy drinker so these problems only exacerbated his alcoholism.

He hit the bottle particularly hard as a result of the physical and emotional injuries he sustained in WWI – injuries that plagued him for the rest of his life.

The Cubs manager Joe McCarthy grew tired of Alexander and his insubordination, that were probably linked to his epilepsy, and sold him to the Cardinals in the middle of the 1926 season.

The Cardinals manager and superstar right handed hitter Rogers Hornsby was more than happy when General Manager Branch Rickey decided to get him as he knew that whilst he hit Alexander well, very few did.

He said he wanted him and that he “didn’t care if he drinks or not.”

The Cardinals would reach the World Series that year for the first time and would face the New York Yankees who were in their fourth World Series in six years.

Alexander pitched complete game victories in games 2 and 6 of the Series, 6-2 and 10-2 respectively. The latter victory forced a deciding game 7, after which Alexander went out drinking.

The deciding game 7 was to be played the next day and the Cardinals starting pitcher that day was Jesse Haines and Alexander was in the bullpen nursing a hangover.

During the bottom of the 7th the Yankees loaded the bases with the Cardinals leading 3-2 and Haines was relieved and Hornsby decided there was only man he wanted to come out of the bullpen and that was Alexander.

So the bases were loaded, 2 out and up to bat was Tony Lazzeri, who was an RBI machine for the Yankees.

Alexander and Hornsby spoke with each other on the mound about what Alexander was going to throw and Alexander told Hornsby that he was going to pitch a fastball inside and then two curveballs away.

Hornsby was horrified and their exchange went like this:

Hornsby: “You can’t throw him a fastball, he’s a fastball hitter!”

Alexander: “If I put it where I want to put it he’s going to hit it foul if he hits it at all.”

Hornsby relented and said:

“Who am I to tell you how to pitch?”

The first pitch was a curveball taken for a strike then Alexander threw an inside fastball which he got lucky with as Lazzeri hammered it down the LF line but marginally went foul after appearing to be heading fair until the last moment.

Alexander then threw another curveball across the outside corner of the plate which Lazzeri swung and missed on for strike 3 ending the threat and keeping the Cardinals in the lead.

The Cardinals failed to score in the 8th but Alexander got the Yankees in order in their 8th. In the 9th the Cardinals again failed to score so the score was still 3-2 in their favour heading to the bottom of the 9th.

Alexander got the first 2 Yankee hitters and was very careful with Babe Ruth and eventually walked him. Ruth then inexplicably decided to try and steal 2nd but was thrown out and the game was over and the Cardinals had won their first Championship.

This story shows the curious nature of sports in my view. As I have already said Alexander has the joint 3rd most number of wins for pitchers ever of 373 but he is arguably remembered most for this 7 out save.

Murderers’ Row

Babe Ruth had been a Yankee star since 1920 but they had only won 1 World Series (against the Giants), losing in 3 others (2 against the Giants). This changed however in 1927 when the Yankees put together what many baseball scholars still believe to this day, the greatest MLB team of all time.

The Yankees were in first place in the AL from the first game of the season to the last and finished the season with a 110-44 record, a full 19 games ahead of 2nd place and it also set a new record of wins in a regular season by an AL side beating the 105 wins the Boston Red Sox won in 1912.

Murderers’ Row was the nickname given to the first 6 hitters of the Yankee lineup: Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri.

The term Murderers’ Row was originally coined in 1918 by a sportswriter to describe the pre-Babe Ruth Yankee lineup of 1918.

Here’s some stats of that ridiculous 1927 team:

- As a team their batting average was .307, slugged .488, scored 976 runs, and had a run differential of 371 runs.

- CF Earle Combs had a career best year, batting .356 with 231 hits.

- LF Bob Meusel batted .337 with 103 RBI.

- 2B Tony Lazzeri batted .309 with 102 RBI.

- 1B Lou Gehrig had a line of .373/.474/1.240, with 218 hits, 52 doubles, 18 triples, 47 home runs and a then record 173 RBI.

- Ruth had a line of .356/.486/1.258, 164 RBIs, 158 runs scored and walked 137 times.

- The pitching staff led the league in ERA at 3.20.

- Waite Hoyt went 22-7 which was tied for the league lead, Herb Pennock and Wilcy Moore got 19 wins each with Urban Shocker close behind with 18.

- Moore, Hoyt and Shocker were the top 3 in ERA in the AL with 2.28, 2.63 and 2.84 respectively.

The Yankees would face the Pittsburgh Pirates in that year’s World Series and it was clear from the outset that it would be no contest as the Yankees won 4-0 with scores of 5-4, 6-2, 8-1 and 4-3.