In 1930, just months after the stock market crashed, Babe Ruth signed a 2-year contract worth $80,000 (approximately around $1.1m today) per year.

This was more money than any player had been paid in the history of the game.

When a journalist asked him if it was unseemly in the midst of the depression to be getting a bigger salary than President Herbert Hoover, he answered:

“Why not? I had a better year than he did.”

The Called Shot

This refers to an incident in the 1932 World Series between the Cubs and the Yankees.

Bit of background first. The Yankees manager Joe McCarthy was a former Cubs manager who took them to the World Series in 1929 but was sacked near the end of the 1930 season, so there was friction between the two teams.

Throughout the series Babe Ruth was getting a lot of stick off the Cubs bench with them according to one of the Cubs players many years later calling “big fat guy” and “slob”. Sledging in those days was not that intelligent clearly!

However more seriously, Ruth and his wife were spat on by Cubs fans on their way in and out of their hotel.

Things came to a head in Game 3 of the World Series where a hotly contested moment happened in the 5th inning when Babe Ruth came to bat with the score at 4-4 having hit a 3 run homer already.

He took 2 pitches for strikes and then before the 3rd pitch he allegedly pointed towards the CF fence “calling his shot” and then proceeded to hit it out.

The origin of this story came from a journalist named Joe Williams that wrote this headline that appeared in the New York World-Telegram, evoking billiards terminology: “Ruth calls shot as he puts home run no. 2 in side pocket”, and the story went on from there. Even journalists not even at the game were reporting it as if they had seen it.

Here’s footage of it. Note his reaction after the home run especially, which he was aiming at the Cubs bench.

As you’d expect both teams and their players played the expected line with the Yankee players saying that he called the shot with the Cubs players shaking their heads and saying “nonsense”.

The pitcher who was at the receiving end of this was Charlie Root and he believed it to be nonsense. He said if he saw Ruth do that he’d have put him on his backside. Charlie Root is a poor soul in all this in my view.

He had a magnificent career and still holds the record of the most number of wins for a Cubs pitcher with 201, yet this is what he most remembered for, which is often the case in sport that we remember the negative(s) about a sportsman’s career more than what they did well.

According to Root’s daughter Della, two days before his death he told her, “I gave my life to baseball, and I’ll only be remembered for something that never happened”.

In the 1970s, a 16mm home movie of the called shot surfaced and some believed it might put an end to the decades-old controversy. The film was shot by an amateur filmmaker named Matt Miller Kandle, Sr.

Only family and friends had seen the film until the late 1980s.

The film was taken from the grandstands behind home plate, off to the third base side. You can clearly see Ruth’s gesture, although it is hard to determine the angle of his pointing.

Some contend Ruth’s extended arm is pointing more to the LF direction, toward the Cubs bench, which would be consistent with his (continued) gesturing toward the bench while rounding the bases after the hit.

Others who have studied the film closely assert that in addition to the broader gestures, Ruth did make a quick finger point in the direction of Cubs pitcher Charlie Root, or CF just as Root was winding up.

In 1999, another 16mm film of the called shot appeared. This one had been shot by inventor Harold Warp, and coincidentally it was the only major league baseball game Warp ever attended.

Warp’s film has not been as widely seen by the public as Kandle’s film, but those who have seen it and have offered a public opinion on the matter seem to feel that it shows Ruth did not call his shot.

The film itself shows the action much more clearly than the Kandle film, showing Ruth visibly shouting something either at Root or at the Cub dugout while pointing.

The authors of the book Yankees Century also believe the Warp film proves conclusively that the home run was not at all a “called shot”.

However, Leigh Montville’s 2006 book, The Big Bam, asserts that neither film answers the question definitively.

My humble opinion is that he definitely did not call it and it’s far more likely that he was pointing towards the Cubs bench.

First ever All-Star Game

It was 1933 and 4 years after the stock market crashed but teams were still struggling to make ends meet, some forced to sell off their best players just to survive, whilst attendances dipped to their lowest levels in decades.

Only the Yankees and a handful of other teams were profitable.

The Minor Leagues were worst affected with over half going out of business. Desperate to lure back paying customers, minor league owners tried dozens of innovations and promotions including:

- Mortgage Nights

- Beauty Contests

- Grocery Giveaways

- Raffles

- Night Baseball

- Cow Milking Contests

In 1933 the majors got in on the act, staging a game at the White Sox’ Comiskey Park on 6th July between the best players in each league to try to revive interest in baseball. Fans across the country were encouraged to vote for their favourites.

It was the very first All-Star Game and of course Babe Ruth was the star as he hit a 2 run homer, the first home run in All-Star Game history, as the AL won 4-2 over the NL.

The first All-Star Game was a commercial success and it was decided that this would become a yearly tradition.

Carl Hubbell and the 1934 All Star Game

The second All-Star Game, held at the Polo Grounds in New York, was famous for the performance of New York Giants left handed pitcher Carl Hubbell.

Hubbell did not start well after giving up a single and a walk but then proceeded to strikeout five of the game’s best hitters: Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons and Joe Cronin, in succession.

The AL however, went on to win the game 9-7.

The Gashouse Gang

“The Gashouse Gang” was the name given to the 1934 St. Louis Cardinals. They went 95-58 that year and played the Detroit Tigers in the World Series.

They had this nickname due to their aggressive, rough and tumble style of play. Frank Graham from the New York Sun said their uniforms were:

“stained, dirty, patched and ill-fitting. They don’t shave before a game and most of them chew tobacco. They spit out of the sides of their mouths, then wipe their hands across their shirt fronts. They’re not afraid of anybody.”

The game had never seen a team quite like “The Gashouse Gang”, a perfect symbol for a country down on its luck. They were daring, hot headed, raucous and unstoppable.

They were the carefully crafted creation of General Manager Branch Rickey and his revolutionary farm system which I talked about in my last story.

They were led by second baseman Frankie Frisch who was celebrated for his furious reactions to bad calls and he considered any call against the Cardinals as a bad call!

He hurled his glove into the air, leaped up and down on his cap until his spikes had shredded it. At least once this proved so persuasive that the umpire reversed and called for a game to be replayed.

Leo Durocher was a brash and cocky shortstop and good in the field but so bad with the bat that Babe Ruth named him in “The All-American Out”.

Left fielder Joe Medwick was called “Ducky” because he ran like one, swung at almost everything but connected enough to lead the league in RBIs three seasons running and to win the NL Triple Crown in 1937.

Third baseman Pepper Martin was a fierce competitor who liked to put sneezing powder into hotel ventilation systems.

However, the most famous member of the Cardinals was a cocky right handed pitcher by the name of Jerome Dean better known as Dizzy Dean.

He was a farm boy who had dropped out of school in year 2. He was an 18-year-old itinerant cotton picker when Branch Rickey’s scouts discovered him.

Very self-assured from early on, he said that he would put more people in the park than Babe Ruth. He said that to Rickey before he was even signed!

He averaged 24 wins a season over a 5-year stretch.

Dizzy was the master at drumming up publicity and before the 1934 season began he announced that he and his younger brother Paul would between them win 45-50 games that year. He was correct as Dizzy won 30 and Paul won 19.

The World Series that year was won in 7 games by the Cardinals over the Tigers with Dizzy Dean going 2-1 in the series.

However, there was also another incident in Game 4 involving Dean when the Cardinals got a base hit and the bench was looking around for someone to use as a pinch runner and Dizzy Dean raced to 1st base himself before anyone could stop him and player/manager Frankie Frisch exclaimed: “Who sent him up there?”

The next batter for the Cardinals hit a double play ball and Dean, determined to break up the double play, didn’t slide and he got nailed on the head by the Tigers shortstop Billy Rogell as the latter tried to throw to 1st.

He was taken to hospital and would make a quick recovery to make his start the next day which was his only loss of the series.

The Babe signs off with a bang

By 1935, Ruth’s abilities had begun to wane as well as enduring a couple of humiliating pay cuts. He desperately wanted to manage the Yankees but there was zero chance of that happening and their current manager Joe McCarthy actually stayed as manager until 1946 when he resigned. Jacob Ruppert, the Yankees owner, said to him “but how can you manage a team, when you can’t even manage yourself?”

Ruth was sold to the Boston Braves. They coaxed Ruth with a vague promise about making him manager the following season, however they had no intention of ever giving him the manager’s job and the real reason they wanted Ruth was to get more people to turn up to their games as they were struggling to attract fans.

His last game would come on 30 May but the last sign of his greatness came on 25 May in Pittsburgh when he went 4-4 including 3 home runs.

Those were the last of his home runs. He officially retired on 02 June.

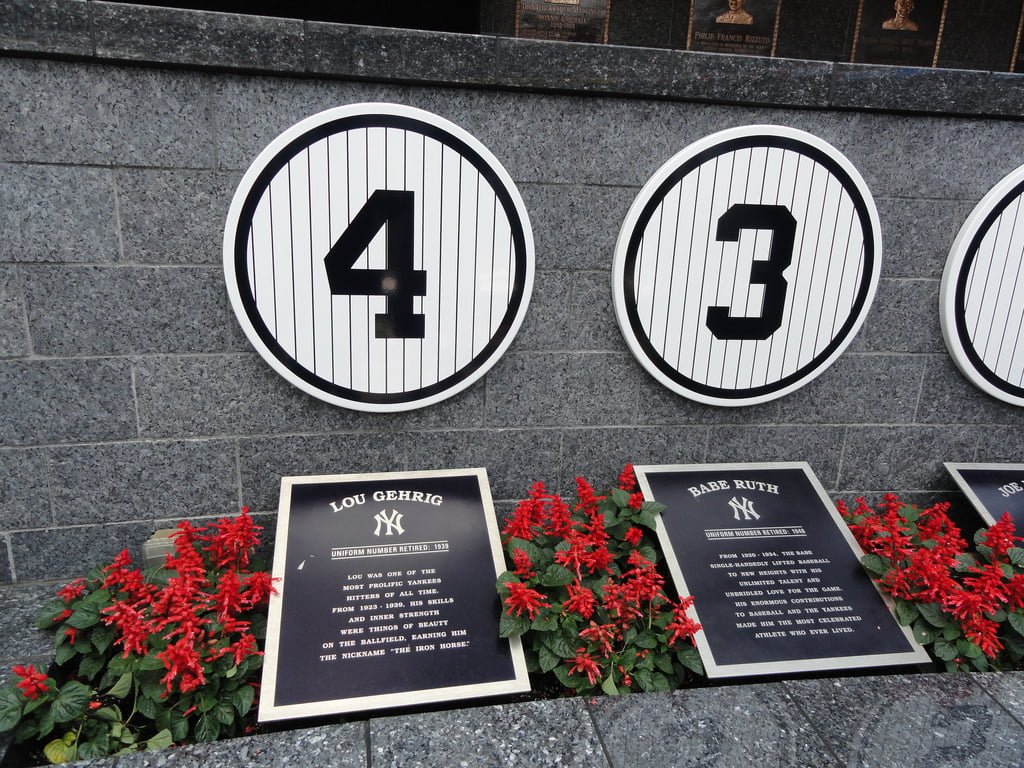

The Iron Horse

On 30 April 1939, Lou Gehrig played his last game for the Yankees and ultimately his career putting an end to his 2,130 consecutive games played streak which was the then record of consecutive games played by 823 games.

He told his manager Joe McCarthy that he was benching himself “for the good of the team.”

The reason he dropped himself was because he was suffering with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Gehrig had a less than superhuman 1938 season although his statistics (.295 batting average, 114 RBI, 170 hits and 29 home runs) were still better than the league average.

When the Yankees turned up for Spring Training in 1939 it was clear Gehrig did not possess his big power anymore and his base running had also massively deteriorated.

By the end of the first month of the season Gehrig’s statistics were appalling with just a solitary RBI and a .143 batting average.

He was only 35, but began to play like an old man, dropping balls, missing again and again at bat, sliding his feet along rather than lifting them.

Gehrig could not understand what was wrong, neither could his teammates, but he could not stand the thought of letting them down, so after a game on 30 April he told his manager Joe McCarthy that he was dropping himself. He would never play again.

As Gehrig’s debilitation became steadily worse, his wife Eleanor called the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Her call was transferred to Charles William Mayo, who had been following Gehrig’s career and his mysterious loss of strength. Mayo told Eleanor to bring Gehrig as soon as possible.

Gehrig flew alone to Rochester from Chicago, where the Yankees were playing at the time, arriving at the Mayo Clinic on 13 June 1939.

After six days of extensive testing at Mayo Clinic, the diagnosis of ALS was confirmed on 19 June 1939, which was Gehrig’s 36th birthday. The prognosis was grim: rapidly increasing paralysis, difficulty in swallowing and speaking, and a life expectancy of less than three years, although there would be no impairment of mental functions.

Eleanor Gehrig was told that the cause of ALS was unknown but it was painless, non-contagious, and cruel—the motor function of the central nervous system is destroyed, but the mind remains fully aware to the end.

On 04 July, Gehrig delivered what has been called “baseball’s Gettysburg Address” to a sold-out crowd at Yankee Stadium:

He often wrote letters to Eleanor, and in one such note written shortly afterwards, said in part:

“The bad news is lateral sclerosis, in our language chronic infantile paralysis. There isn’t any cure, there are very few of these cases. It is probably caused by some germ. Never heard of transmitting it to mates. There is a 50–50 chance of keeping me as I am. I may need a cane in 10 or 15 years. Playing is out of the question.”

If anyone reading has not heard about this disease, this is the disease that the ice bucket challenge in 2014 was all about.

An article in the September 2010 issue of the Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology suggested the possibility that ALS-related illnesses diagnosed in Gehrig and other athletes may have been catalysed by repeated concussions and other brain traumas.

In 2012, Minnesota State legislators sought to unseal Gehrig’s medical records, which are held by the Mayo Clinic, in an effort to determine a connection, if any, between his illness and the concussion-related trauma he received during his career, prior to the advent of batting helmets and other protective equipment.